Natalie Wood Death

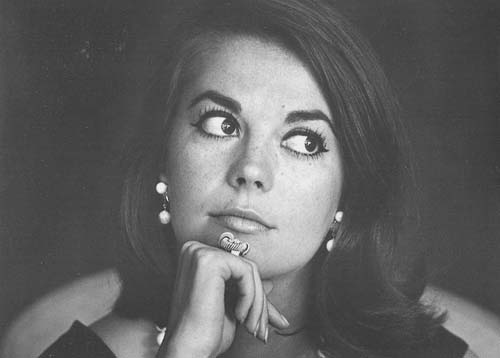

Natalie Wood

More than half way through his biography of Natalie Wood, Gavin Lambert tells us that he first met his subject in 1956. They were introduced by Nicholas Ray, who had directed Natalie Wood in Rebel Without a Cause a year earlier; Lambert had since become Ray's assistant. Nine years later, when Wood wanted to star in the movie of Lambert's novel, Inside Daisy Clover, the pair became good friends. 'I was wondering exactly what was going on with you and Nick Ray,' Wood said over dinner, referring to their first encounter. 'What was going on,' Lambert replied, 'was exactly what you wondered.'

The timing of this revelation is mischievously discreet. We already know that Ray had relieved Wood of her virginity; now, over a hundred pages later, we find out that her biographer himself succeeded her. But to have given this detail any more prominence would have been un-Lambert-like. Readers of his gripping memoir, Mainly About Lindsay Anderson, will already know about Lambert's relationship with Ray, so movingly entwined with the movies. And in writing about Natalie Wood, Lambert has chosen a careful position: one that must contrast with that of the scandalmongers and self-proclaimed intimates who came forward after her mysterious death. It's not until Lambert's final acknowledgments, for example, that we learn that Wood's widower, Robert Wagner, once told him: 'When you tell the truth about Natalie as you see it, I shall be at peace.'

Movie bios often fall into one of three broad categories: the autobiography (ghost-written or otherwise) of the star; the memoir of the star's assistant/butler/lover/child, in which agendas come out of hiding; the workmanlike overview with little critical insight. Lambert, however, is exceptional. He is an insider in Hollywood, where he arrived in time to know Norma Shearer (about whom he wrote a masterly biography) among many others. But he is also a critic (Lambert edited Sight and Sound for most of the 1950s), and in all of his non-fiction he brings a critic's eye to materials to which only an insider would be granted access: letters, diaries, the testimony of close relatives and friends. Lambert has equal respect for history and human beings; this biography is stunning not merely because he reveals new facts but because of his ongoing relationship to facts: he is sceptical, elegant, generous, exact.

Natalie Wood was propelled into stardom at the age of seven, by an ambitious mother who demanded that she 'make people love' her, in order to support her Russian immigrant family. She appeared opposite Orson Welles in Tomorrow Is Forever, and is still remembered as the little girl in Miracle on 34th Street. She continued to act in 'family pictures' as her own family disintegrated (her alcoholic father once waved a knife at her pregnant mother's stomach) or went unacknowledged: when her father, a studio carpenter, appeared on set to repair a piece of furniture, her mother warned her never to say hello to him in those circumstances again.

Then she met Nicholas Ray and Dennis Hopper and had affairs with both of them. 'When I think about those early days with Natalie,' Hopper told Lambert, 'the cool way she handled two affairs at the same time - I realise Natalie was way ahead of her time.'

After Rebel Without a Cause, she went on to give another Oscar-nominated performance in Elia Kazan's Splendor in the Grass. She was a lovestruck teenager in West Side Story, and an awkward girl turned high-class stripper in Gypsy. To each of these roles she brought a mixture of sweet-eyed serenity and nervy despair.

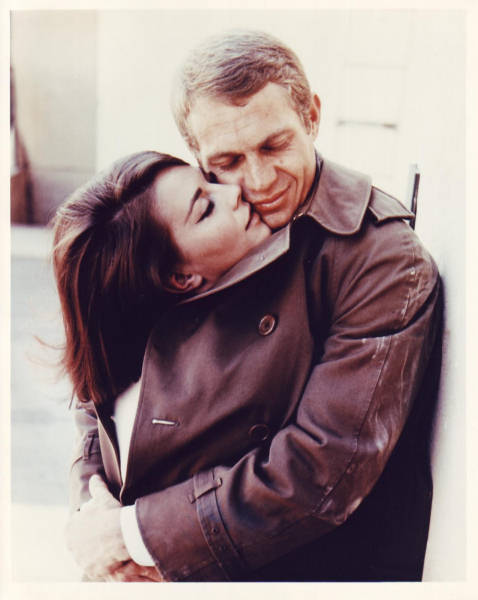

When she was 10 years old, she came across a 19-year-old actor on the lot at Fox studios, and instantly fell in love with him. By the time she made Rebel Without A Cause, Robert Wagner's fan mail was, according to Lambert, 'second only to Marilyn Monroe's'. They were married in 1957, and became one of the brightest star couples in Hollywood.

'My husband, my child, my strength, my weakness, my lover, my life,' Natalie Wood wrote of Robert Wagner a year into their marriage. Lambert tells this extraordinary love story with great empathy, and a good deal of help from Wagner.

The couple bought a house, and planned to decorate it in such grand style that it was never finished. When Lambert met them, they seemed to him 'not quite real, like the house. Later, I wondered if they seemed that way to themselves.' Eventually, their marriage fell apart. 'They were paralysed by simultaneous but separate insecurities,' Lambert writes, 'a couple who still loved but no longer understood each other, or themselves.'

Wood took refuge in other affairs; Warren Beatty, Nicky Hilton, and later, Frank Sinatra. One co-star remembers her 'working a room in search of love'. Wagner remarried and had a child. Wood attempted suicide (twice). She remarried and had a child. Then, in July 1972, they both remarried and had a child - with each other. 'The first time round, you sometimes got the impression they were playing it,' one friend told Lambert. 'But this time they just enjoyed letting people see how happy they were.'

One crucial protagonist in the Natalie Wood story refused to break his silence. Christopher Walken, with whom Wood may or may not have been having an affair when she died, and who, along with Robert Wagner, was with her the night she drowned, or drowned herself, at the age of 43. Towards the end of her life she took a regular cocktail of drugs - pain medication, sleeping pills - and a fair bit of drink. But many people who saw her around that time felt she was upbeat. She was very close to her two young daughters and maintained a dry sense of humour.

by Gavin Lambert

No comments:

Post a Comment